Ever since the Internet became a commercial entity, hackers have used it to impersonate companies through a variety of clever means. And one of the most enduring of these exploits is the practice of typosquatting, or the use of similar websites and domain names to lend legitimacy to social engineering efforts.

These lookalikes exploit users’ carelessness in checking legitimate websites and sometimes rely on human errors, such as placing a typo in a URL, to catch victims. Some of these domains have small, intentional spelling errors, such as adding a hyphen or substituting similar-looking characters; one of the first typo-prone domains, for example, was Goggle.com, which was quickly removed when it was discovered by Google.

But even though the tactic has been around for decades, attackers are becoming increasingly sophisticated and learning how to better disguise their domains and fake messages to be more effective at spreading malware and stealing data and funds from careless users.

Typosquatting attacks on the rise

The continued prevalence of typosquatting was recently demonstrated by a worrying fact spike in Bifrost Linux malware variants in recent months using fake VMware domains. But there are also many other recent examples of typosquatting attacks.

These include the emergence of scam sites that are based on brand impersonationa series of fake websites for hiring jobsphishing attempts from the SolarWinds supply chain attackers in 2022 and scammers abusing X’s paid badge system in 2023, among many others.

Renée Burton, head of threat intelligence at Infoblox, tracked these criminals. Infoblox telemetry, which analyzes billions of network data points every day, identifies more than 20,000 such domains weekly.

“The real threat to users and businesses globally comes from artfully created lookalike domains, which means there is no accident,” he explains. “A criminal is making a deliberate choice to try to trick someone. They can be very convincing to a user and are difficult to spot, especially in small browser fonts. Many of them go unnoticed.”

Typing criminals are constantly perfecting their craft in what appears to be a never-ending cat-and-mouse conflict. Several years ago, researchers have discovered the homograph trick, which replaces hard-to-distinguish non-Roman characters when they appear on screen. For example, instead of using “apple.com” in a URL, a criminal will construct his homograph with the code “xn–80ak6aa92e.com,” which uses Cyrillic characters instead. Since then, all modern browsers have been updated to recognize these homograph attack methods.

In an Infoblox story last April titled “A Deep3r Watch Lookal1ke attacks“, the authors of the report state that “everyone is a potential target.”

“Low prices for domain registration and the ability to deploy large-scale attacks give actors an advantage,” they wrote in the report. “Attackers have the advantage of scalability, and while techniques for identifying malicious activity have improved over the years, defenders struggle to keep up.”

For example, the report shows increasing sophistication in the use of typosquatting lures: not just for phishing or simple fraud, but also for more advanced schemes, such as combining websites with fake social media accounts, using of nameservers for major email spear-phishing campaigns, creating fake cryptocurrency exchange sites, stealing multi-factor credentials, and replacing legitimate open source code with malicious code to infect unsuspecting developers.

An example of the last point is how attackers exploited “requests,” a very popular Python package with over 6 million downloads per day. “Packages with names like ‘requeststs,’ ‘requeests,’ ‘requuests,’ ‘reqquests,’ ‘reequests,’ and ‘requests’ were spotted” by Unit42 researchers, according to the Infoblox report.

Criminals have also become more reactive to news events, such as creation of fake sites to collect donations for earthquake relief. And recently a new turning point occurred found by Akamai, focusing on the hospitality industry. These were scammers replicating hotel booking pages for the initial phishing campaign, then stealing credit card information from potential guests’ reservations. Criminals added subdomain phrases like “booking” or “support” to their occupied domains to make them appear more credible.

Stijn Tilborghs, Akamai’s chief data officer, says: “I would have fallen for this particular exploit. You have to be really paranoid to suspect an attack.”

How to fight typosquatting

Already in 2014, an article presented at a USENIX conference by Janos Szurdi, entitled “The long ‘tail’ of typosquatting domain names” (note the intentional typo), found that by examining thousands of websites, including the least visited ones, typosquatting was widespread and targeting a wide range of domains.

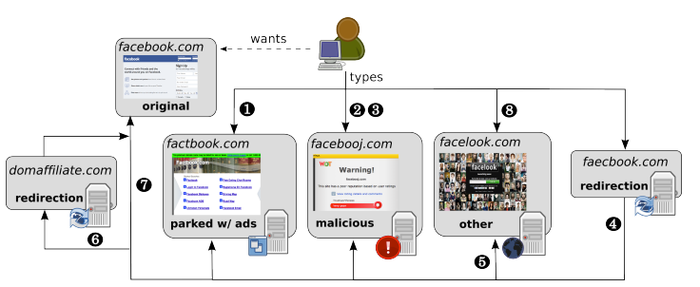

Szurdi found that the practice has increased over time and that domain squatters invest significant resources in managing their criminal activities. The document maps their ecosystem as shown below, including 1) incoming traffic, 2) creation of phishing pages, 3) delivery of malware, and 4) redirection to alternate domains and other methods.

The typosquatting ecosystem with various ways criminals can generate funds. Source: Janos Szurdi via USENIX.

The long history of typosquatting brings with it an important lesson for IT professionals: be aware of injection attacks within an enterprise web infrastructure. Every element of every web page can be compromised, even small, rarely used icon files. It helps you pay more attention, especially when browsing websites on mobile devices.

But there are several protective measures that can be implemented by businesses. One way is to use one of the many alternative domain name service providers, such as OpenDNS and Google DNS. These include exploit-aware typosquatting protection for larger web destinations. However, these protections cannot keep up with the thousands of new misspelled domains registered every day.

Another recommendation is to use enterprise security tools to carefully examine log access files. Additionally, security awareness training exercises are helpful in making users aware of various ways to recognize the exploit.

“No one company can capture everything,” says Akamai’s Tilborghs. “Multiple layers are needed. And always be very cautious. The bad guys have an advantage. They can send an attack to thousands of domains and count on some of them to get through.”

Part of the problem, as mentioned in the 2014 USENIX paper, is that “it is not possible to easily classify a new recording as an example of typosquatting based on its name alone.” This is where companies like Akamai and Infoblox have implemented a combination of automated and manual detection methods into their tools. However, all it takes is one distracted employee to become a victim.

“Typosquatting has long caused annoyance to Internet users. Because users lack effective countermeasures, speculators continue to register domain names to target domains and exploit the traffic that comes from mistyping those domain names,” they wrote the USENIX authors in their report, a statement that still holds true today.