There’s a physical education teacher in Portland, Oregon, who spends Wednesday mornings leading a gaggle of kids to school on bicycles.

Watching them speed through the city: their helmeted heads bobbing in unison to the music coming out of a speaker; joggers and crossing guards smile as they pass – it’s a raucously joyous sight. Millions of people tuned in, thanks to social media, and a “Coach Balto” camera he takes with him on the trip.

On the other side of the country, a group of New Yorkers who meet in a Brooklyn basement to sing multi-part harmonies to Sia songs and tunes has also wooed the masses online. And in Los Angeles, the near-constant livestream of a woman handing out food and hygiene products from the back of her van to the homeless on Skid Row has been a social media superstar for five straight years.

Collectively, we are all a little baffled by the residual effects of the pandemic and the two-plus years of mandatory agoraphobia it has subjected us to. Economic uncertainty (among other anxieties) is also taking up a lot of shared brain space these days, and these little bits of human connection make for a welcome palette cleanser.

At the same time, almost as a side effect, these recorded vignettes of communities forming in real time have managed to put an extremely fine point on something that economists, urban planners and publications like Money have been grappling with for a long time. What, exactly, makes a point look like a dot on the map? somewhere? That is, what distinguishes a place from people Want live of a people Have live?

It’s not about the square footage of an average home or the scenery that surrounds it. What truly makes a place a place it’s a sense of belonging, driven by the powerful energy of people who want to be part of something bigger than themselves.

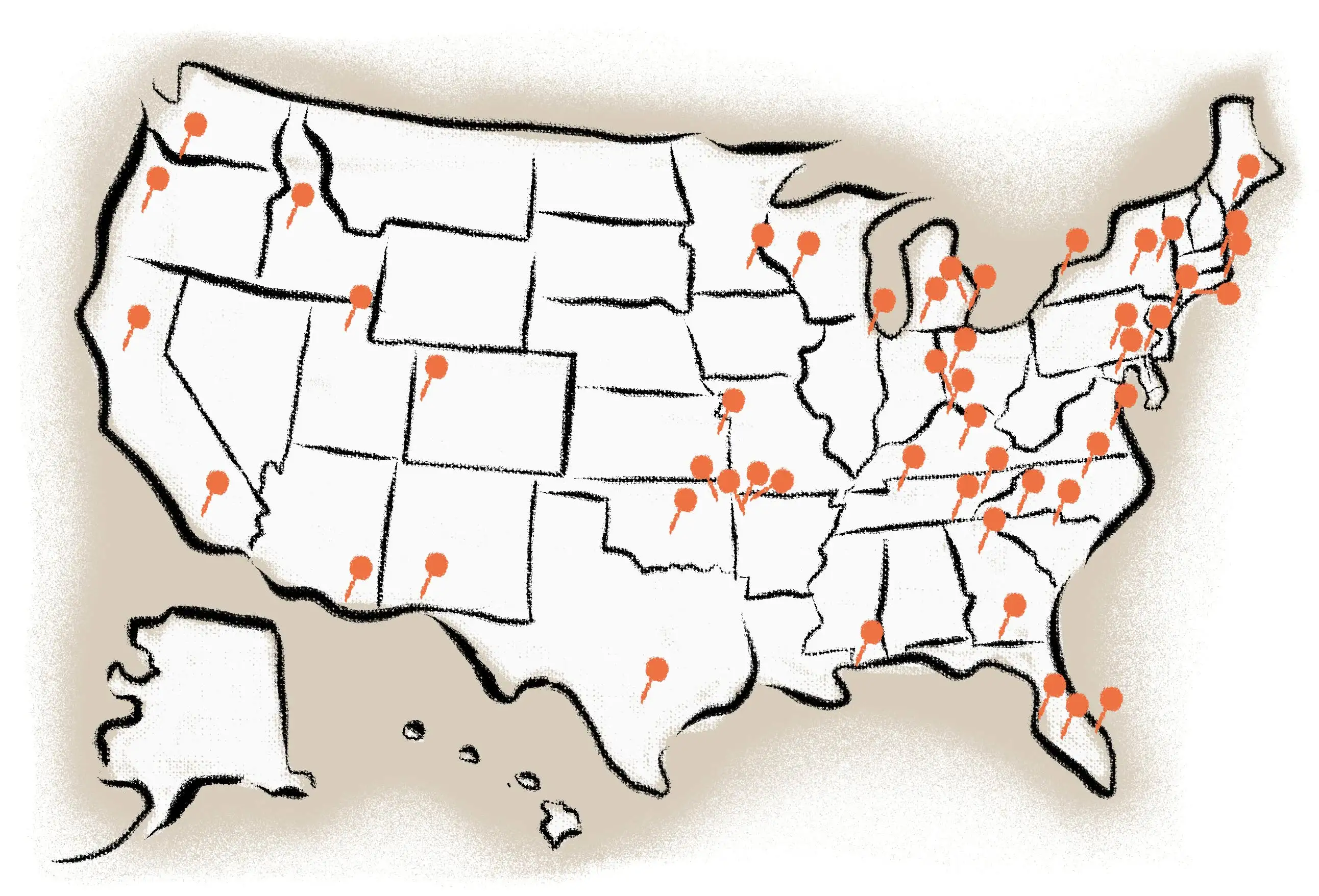

This year The best places to live it’s not just a question of numbers. We’ve chosen 50 cities and towns that offer affordability, good schools and strong job markets. But above all, these are places with a palpable spirit, cultivated and supported by engaged citizens and receptive public officials.

Take Oklahoma City.

Twenty years ago, downtown OKC was dominated by a tangle of parking lots and sterile office buildings. Nobody went there unless they absolutely needed to, so outside of the 9-to-5 routine, the urban core of Oklahoma’s largest metro was virtually desolate.

To revive its stagnant economy in the mid-1990s, Oklahoma City embarked on a serious, high-profile campaign to bring United Airlines’ new headquarters within its borders. But since this was Oklahoma City in the mid-1990s, the airline opted for Indianapolis instead.

Taking this rejection as a sobering wake-up call, city officials launched a series of extremely ambitious redevelopment projects, collectively dubbed MAPS (Metropolitan Area Projects). Just a few months later, domestic terrorist Timothy McVeigh detonated a homemade bomb in the city center, killing 168 and reducing an already battered swath of downtown to rubble.

This, by all accounts, should have been impossible to recover from. Yet today, Oklahoma City is more alive than it has ever been.

A gleaming mile-long canal now carves a path through a city center once overwhelmed by rust, and teems with water taxis carrying vacationing families and giddy locals on first dates. Pedestrian neighborhoods with widened sidewalks have replaced dangerous one-way streets, and a seven-mile stretch of river that was once so neglected municipal landscapers have had to periodically mow patches of vegetation that were encroaching on it. It now hosts competitive rowing events, river cruises and kayak trips. It’s also one of the fastest-growing metro areas in the United States, with a booming job market and affordable cost of living that consistently earns accolades from Kiplinger, U.S. News, Zillow and others.

OKC wiped the slate clean and rebuilt itself from the ground up using the MAP plan as fuel. But make no mistake: Oklahoma City residents have been the driving force behind its transformation.

Unlike conventional urban development initiatives, OKC residents vote directly on proposed projects, determining which ones get the green light. Approved projects are then overseen by a citizen advisory board and are funded by a city sales tax also set by voters, allowing MAPs to exist outside the constraints of the municipal budget and the machinations of political agendas. Oklahoma City residents have approved $2.83 billion in investments in their city since 1993, according to a report from Harvard University’s Data-Smart City Solutions project, and that money has facilitated the construction of public schools, the performing arts and everything in between.

Together, as a unified community, OKC residents and politicians have built a livable, walkable city with a distinct identity; a living, breathing organism powered by more than just cars and conference calls. It is a remarkable transformation and not an isolated one.

Across the United States, cities and towns are taking extraordinary steps to cultivate a sense of “place,” and much of the transformation is being driven by engaged citizens themselves.

In Detroit, a growing group of neighborhood “block clubs” are harnessing the power of time-tested grassroots initiatives like phone trees and community lunches to promote redevelopment, beautification and crime prevention. Likewise, the city has won numerous urban planning awards for revitalization efforts that put locals at the center of attention. Detroit’s YOUTH-CENTRIC Neighborhood Framework project, in which a local youth council worked side-by-side with city leaders, community organizations and design firms to build the framework for changes planned for residents in Cody Rouge neighborhoods and Warrendale in Detroit. The city is also home to Outlier Media, a nonprofit online newsroom that publishes service journalism focused on “navigating and understanding life in Detroit.” The most popular guides on the site include “How to Follow the Money in the Country,” “How to Buy a House with Cash,” and, fittingly, “How to Start a Block Club in Detroit.” Eleven years after filing for Chapter 9 bankruptcy — the largest in U.S. history — the city is rapidly attracting tourism, venture capital and real estate investment.

Metuchen, New Jerseya New York commuter town, once drifting toward suburban monotony, has spectacularly transformed into the modern version of a Norman Rockwell painting in less than a decade.

Thanks to the Metuchen Downtown Alliance, a local nonprofit, the once-sickly city is now full of life; invigorated by a diverse group of neighbors who pop in and out of locally owned ice cream parlors, boba bars and tequila bars. A packed calendar of cultural events draws scores of visitors to its postcard-perfect downtown, who flock to Metuchen to celebrate Restaurant Week, Lunar New Year and more. (Last year, Metuchen hosted a Taylor Swift-themed dance party for teens and a professional wrestling rumble, among others.)

Of course, none of this is helpful to residents who can’t make ends meet. For locals, it doesn’t matter how impressive your municipal parks are or how many cute cocktail bars are popping up downtown, if they don’t have the time or disposable income to make use of them. The inescapable reality of life in the United States in 2024 is that no matter where you live, As live is inextricably linked to the relationship between how much money you earn and how much your rent or mortgage costs. And that delicate balance is likely to shift when an influx of new residents decide they, too, want to call your community home.

No place is immune to these challenges, but the most resilient ones, the “best” ones, are facing the dichotomy between long-time locals (typically from historically marginalized and disadvantaged communities) and newcomers (a huge portion of whom will likely be affluent, white, and highly educated) with infrastructure and policies designed to push the city forward while ensuring no one is left behind.

In Detroit, a new down payment assistance program is lowering financial barriers to the housing market. The initiative builds on the success of the city’s 0% interest home repair loan program, which provides much-needed support to homeowners struggling with the costs of maintaining their properties.

In Boise, where an influx of newcomers has driven up housing costs for locals, a nonprofit mortgage broker called NeighborWorks Boise has built “pocket neighborhoods” of mixed-income housing made up of energy-efficient single-family homes oriented around open green spaces that homeowners work together to maintain. As a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI), Neighborworks also provides below-market home loans and down payment assistance to families living in these homes.

Oklahoma City has also found itself facing the familiar threat of dwindling affordable housing stock in the wake of its revitalization, and a number of public initiatives are working to address this problem. Pivot Inc., a local nonprofit, has built dozens of tiny houses in the city to serve as temporary housing for young people experiencing homelessness. The latest version of the city’s MAPS program is converting a former Motel 6 into additional housing units for the homeless population, along with a wide range of affordable housing initiatives for low- and moderate-income families. Other MAP projects underway for 2024 and beyond include new community parks and gardens, a senior wellness center, additional improvements to sidewalks, bike lanes and walking trails, and dozens more.

For places like this, the pursuit of a livable, equitable revival – one that benefits all who jog in its parks, dine in its cafes and move through its streets – is an ongoing challenge. But it’s a test that some cities are passing with flying colors and, in doing so, are demonstrating unequivocally that every place has the capacity to become a “better place.”