As tensions in the Middle East continue to rise, cyber attacks and operations have become a standard part of the fabric of geopolitical conflict.

Last week, the head of Israel’s National Cyber Directorate accused Iran and Hezbollah of “round-the-clock” cyberattacks against the country’s networks, government agencies and businesses, tripling in intensity as Israeli military operations continued against Hamas in Gaza. After Quds Day – Iran’s commemoration of the pro-Palestinian Jerusalem Day on April 5 – dozens of denial-of-service attacks disrupted Israeli targets, according to data from cybersecurity firm Radware.

Even though the volume of cyber attacks has remained at a lower level this year, renewed tensions between Israel, Iran and Lebanon could easily lead to increased cyber activity, says Pascal Geenens, director of threat research for Radware, a vendor with based in Tel Aviv. of security solutions in the cloud.

“There are two planes we need to consider here,” Geenens says. “One is more aligned to the nation-state, meaning it purposely attacks another nation, while the other is all hacktivist activity – they just want to share their message [and] demonstrate that they are not happy with the situation.”

Overall, Israel should be ready for more destructive cyber attacks, as Iran and other regional cyber groups have shown little restraint in such attacks, Google concludes in its “Tool of first resort: the war between Israel and Hamas in cyber” report, published in February. While Iran and Hezbollah appear poised to use destructive cyberattacks against both Israel and the United States, Israel-linked groups will likely continue to target Iran, and hacktivists will likely target targets any organization they believe is associated with their perceived enemies, the report states.

“We assess with great confidence that Iran-linked groups will likely continue to conduct destructive cyberattacks, particularly in the event of a perceived escalation of the conflict, which could include kinetic activity against Iranian proxy groups in various countries, such as Lebanon and Iran. Yemen,” the company said in the report.

Not your father’s cyber conflict

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the Russian military used cyberattacks to target Ukraine before and during the invasion, and widely attacked the United States and Ukraine’s allies in Europe over the next two years at the beginning of the war.

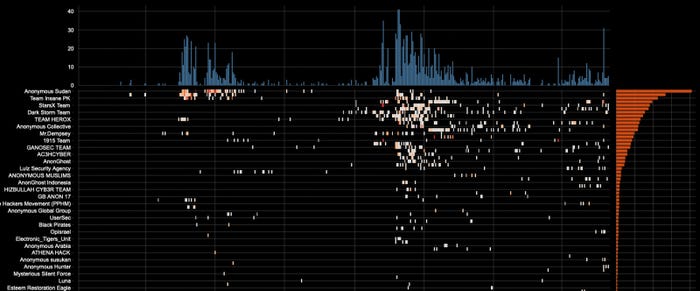

A significant spike in cyberattacks occurred before and after October 7, while much more modest levels of activity have targeted Israel this year. Source: Radware

For the Middle East, cyber conflict has a different character. On the one hand, conflict participants have different strengths and limitations, which influence their options and make cyber conflict more asymmetric. Where the Russian government has unity of purpose, Iran and Hamas are more opportunistic adversaries. Where Russia and Ukraine have similar cyber capabilities, Israel’s military operations have limited Hamas’ ability to respond and the country has the most sophisticated cyber attack capabilities in the region, says Ben Read, head of cyber espionage analysis for the Google Cloud’s Mandiant incident. response group.

“Iran is very opposed to Israel, but it is not a direct party to the conflict, so its goals are not necessarily to support the conquest of territory in the same way as Russia,” he says. “Because conventional weapons are not [currently] an acceptable outcome for Iran, they are using cyber to do something destructive [operations]. … Cyber may be an easier tool to reach there.”

Iran is not the only anti-Israeli actor in the region. Google has observed cyber operations by groups linked to Hezbollah, a Lebanese Islamic political party and militant group aligned with Iran.

Iran it has also been the target of disruptive cyber operations in the context of conflict, says Kirsten Dennesen, an analyst in Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG). Several disruptive attacks on the nation’s infrastructure have been attributed to Predatory Sparrow, which reappeared in October AND attacked Iranian gas stations in Decemberand which some analysts have linked to Israel.

“Telegraphing intentions and demonstrating involvement in the conflict without escalating or directly taking part in the confrontation on the ground… limits the potential backlash while simultaneously giving regional actors the opportunity to project power through the cyber domain,” he says. “Furthermore, cyber capabilities can be rapidly deployed at minimal cost by actors who may wish to avoid armed conflict.”

Rebirth of hacktivism

Nation states are not the only actors involved in the conflict. Over the past year, hacktivism has taken off as tech-savvy protesters react to the Russia-Ukraine war and the conflict between Israel and Hamas. Much of the increase in attack activity in Israel is due to hacktivism demonstrated by the sharp increase in denial-of-service attackssays Radware’s Geenens.

“It’s not that it didn’t exist before, but before they were much less organized, and now they have this ability to come together on Telegram,” he says. “They all started communicating with each other via hashtags. They find each other much easier, so they band together and create alliances to carry out attacks.”

In the past, groups banded together under the name Anonymous, claiming their nickname and attempting to convince other groups to join. Today they use Telegram operations-specific hashtags to acquire like-minded collaborators, a much more efficient method of operation, Geenens says.

Hacktivism will likely continue to fuel attacks not only against Israel, but also against other countries, he says. Attacks are more likely to escalate rapidly as nation-states develop standard techniques and hacktivists are able to collaborate more efficiently.

“Whatever happens in the future,” Geenens says, “whether it’s a military operation or the outcome of an election that they don’t like or someone says something they don’t like, they will be there and they will be there to be there. wave of DDoS attacks.”