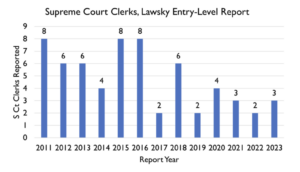

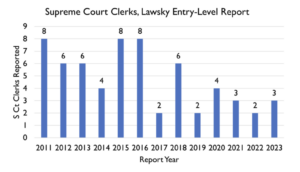

From 1940 to 1990, about one-third of Supreme Court clerks became law professors. But in recent years, Brian Leiter and Jeff Gordon note, that percentage has declined considerably. Sarah Lawsky has some numbers of employees who have entered academia in the last decade or so that Brian recently posted:

While Sarah is missing some former employees from her numbers, that’s a notable drop. What explains the trend? In the comments on Brian’s post, Professor Dan Epps has a suggestion that I think explains a lot: the growing separation between the law clerk track and the law professor track.

I realize this is a niche topic, but here’s a little background to explain this growing divide for those who may be interested. Decades ago, getting a high-level clerkship and getting a high-level professorship were the same thing. If you were a law student and you wanted to be a law professor, you got the highest grades you could and tried to use your grades to get a clerkship with the most prestigious judge you could. The internship served as a sort of law degree. If you hit the jackpot and clerked for the Supreme Court, it was reasonably likely that it would lead to a professorship at a top law school. Top schools have sought to hire former clerks, with some law school deans visiting the Supreme Court to meet with clerks and propose they become professors at their schools. It was the period from 1940 to 1990, indicated at the top of the post, when about a third of the employees later became professors.

Nowadays, on the contrary, the paths are much more separated. First, there is more than a multi-year planning process for a Supreme Court clerk. Most Supreme Court clerks now have multiple prior clerkships before starting on the Supreme Court: According to David Lat, 29 of the current 36 clerks had two or more clerkships prior to their current positions. And even those are often spaced apart. Simply scrolling through the list on David’s site, it appears that a typical clerk graduated about 3-4 years before starting on the Supreme Court. By the time you’re done with the Supreme Court, you’ve been out of law school for 4-5 years and may only have a year or so of actual law practice left. Meanwhile, big law firms await you with what now appears to be $500,000 bonuses if you join them.

If you want to become a law professor, however, the paths today tend to be different. Law schools are now evaluating potential entry-level professors much more on their scholarship than on their grades or tenure. Basically, you need to have spent a few years researching and writing grants to prepare to go on the market for a tenure-track job. Getting a PhD has become a very common way to develop an academic methodology and start writing some papers. At most top schools that I’m aware of, a clear majority of recent entry-level hires have one. And even if you don’t have a PhD, you’ll probably have to spend two years in law school as a Fellow or Visiting Assistant Professor (VAP), learning the quirky ways of academia and working on a paper or two. to prepare for the entry-level market. As Sarah Lawsky found, about 90% of new hires have a fellowship or doctorate. Many have both.

The bottom line from all of this, in my opinion, is that the single path of decades ago has largely split into two separate paths. Once you’re in law school, the way to maximize your chances of getting a Supreme Court clerkship is different than the way to maximize your chances of getting tenure, especially at a top school. I think this goes a long way to explaining why today we see fewer people succeeding on both paths, first working on the Supreme Court and then becoming academics. It’s not the only explanation. But I think that’s the main one.

As I said before, this is a niche topic. Some readers (if anyone is still reading) may wonder, “Who cares?” And absolutely right if you don’t. This may simply be navel-gazing that has no meaning outside of the faculty room. But I wonder if it might not also be a small sign of a broader change in the role and background of law professors and, consequently, law schools. As Richard Posner noted in the 2007 essay I blogged about last month, over the decades there has been a shift from the model of the law professor as an expert lawyer immersed in the law to the model of the law professor as an academic who writes and teaches in the field of law. I wonder if the declining number of former Supreme Court clerks entering academia might be a small indicator that that shift is continuing.

UPDATE: If there are any recent employees or recently appointed professors (or both) who want to weigh in on this, I’d be happy to post reactions on their sense of this and whether they agree. Happy to also remove names if requested. Just email me or go to Berkeley dot edu.