By Byron Kaye

(Reuters) – Since Meta blocked news links in Canada last August to avoid paying commissions to media companies, right-wing meme producer Jeff Ballingall says he has noticed an increase in clicks for his Facebook Canada page Proud (NASDAQ:).

“Our numbers are growing and we are reaching more and more people every day,” said Ballingall, who posts up to 10 posts a day and has about 540,000 followers.

“The media will become increasingly tribal and niche,” he added. “This just turns it on further.”

Canada has become the staging ground for Facebook’s battle against governments that have enacted or are considering laws that coerce Internet giants — primarily Meta, which owns the social media platform, and Alphabet’s (NASDAQ:) Google. – to pay media companies for links to news published on their site. platforms.

Facebook has blocked news sharing in Canada instead of paying, saying the news has no economic value to its business.

It is seen as likely to take a similar step in Australia if Canberra tries to enforce its 2021 content licensing law after Facebook said it would not extend deals it has with news publishers there. Facebook briefly blocked news in Australia before the law.

Blocking news links has led to profound and disturbing changes in how Canadian Facebook users interact with information about politics, two unpublished studies shared with Reuters have found.

“The news that people talk about in political groups is being replaced by memes,” said Taylor Owen, founding director of the Center for Media, Technology and Democracy at McGill University, who worked on one of the studies.

“The ambient presence of journalism and real information in our feeds, the signals of trustworthiness that were there, have disappeared.”

The lack of news on the platform and increased user engagement with unverified opinions and content have the potential to undermine political discourse, particularly in election years, the study’s researchers say. Both Canada and Australia will go to the polls in 2025.

Other jurisdictions, including California and Britain, are also considering legislation to force internet giants to pay for news content. Indonesia introduced a similar law this year.

BLOCKED

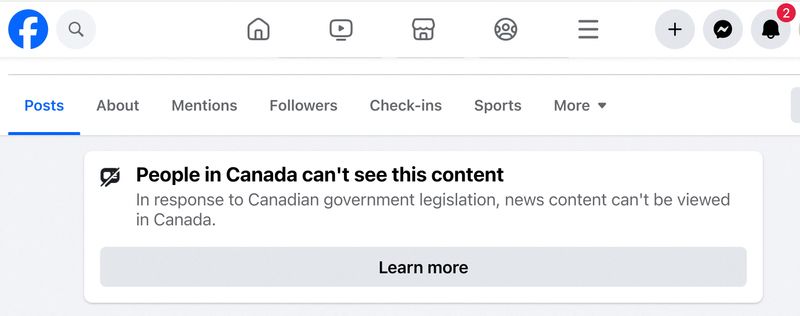

In practice, Meta’s decision means that when someone posts with a link to a news article, Canadians will see a box with the message: “In response to Canadian government legislation, news content cannot be shared.” .

Where news posts on Facebook once garnered between 5 and 8 million views from Canadians per day, according to the Media Ecosystem Observatory, a project of McGill University and the University of Toronto, that number has disappeared.

While engagement with political influencer accounts such as partisan commentators, academics and media professionals remained unchanged, reactions to image-based posts in Canadian political groups on Facebook tripled to match previous engagement with news posts, it also found I study.

The research analyzed around 40,000 posts and compared user activity before and after blocking news links on the pages of around 1,000 news publishers, 185 political influencers and 600 political groups.

A Meta spokesperson said the research confirmed the company’s view that people continue to go “to Facebook and Instagram even without news about the platform.”

Canadians can still access “authoritative information from a range of sources” on Facebook and the company’s fact-checking process is “committed to stopping the spread of misinformation on our services,” the spokesperson said.

A separate NewsGuard study conducted for Reuters found that likes, comments and shares from what were classified as “unreliable” sources rose to 6.9% in Canada in the 90 days following the ban, compared to 2 .2% in the previous 90 days.

“This is particularly concerning,” said Gordon Crovitz, co-chief executive of New York-based NewsGuard, a fact-checking firm that rates websites for accuracy.

Crovitz noted that the change came at a time when “we see a sharp increase in the number of AI-generated news sites publishing false claims and an increasing number of doctored audio, images and videos, including by governments hostile… intended to influence the elections.”

Canadian Heritage Minister Pascale St-Onge, in an emailed statement to Reuters, called Meta’s blocking of news an “unfortunate and reckless choice” that allowed “misinformation and disinformation to spread on the their platform…during need-to-know situations such as fires, emergencies, local elections and other critical moments.”

Asked about the studies, Australian Deputy Treasurer Stephen Jones said via email: “Access to quality, trusted content is important to Australians and it is in Meta’s interests to support this content on its platforms.”

Jones, who will decide whether to hire an arbitrator to determine Facebook’s media licensing agreements, said the government had made clear to Meta its position that Australian media companies should be “fairly remunerated for news content used on digital platforms”.

Meta declined to comment on future business decisions in Australia but said it would continue to engage with the government.

Facebook remains the most popular social media platform for current affairs content, studies show, even though it has been in decline as a news source for years due to the exodus of younger users to rivals and Meta’s strategy of de- prioritize politics in user feeds.

In Canada, where four-fifths of the population is on Facebook, 51% got news on the platform in 2023, the Media Ecosystem Observatory said.

Two-thirds of Australians are on Facebook and 32% used the platform for news in the past year, the University of Canberra has said.

Unlike Facebook, Google has not indicated any changes to its deals with news publishers in Australia and has reached an agreement with the Canadian government to make payments to a fund that will support media outlets.