Cybersecurity researchers are warning of a spike in email phishing campaigns that are using the Google Cloud Run service as a weapon to deliver various banking Trojans such as Astaroth (aka Guildma), Mekotio and Ousaban (aka Javali) to targets in all of Latin America (LATAM) and Europe.

“The infection chains associated with these malware families involve the use of malicious Microsoft Installers (MSIs) that function as droppers or downloaders for the final malware payloads,” Cisco Talos researchers revealed last week.

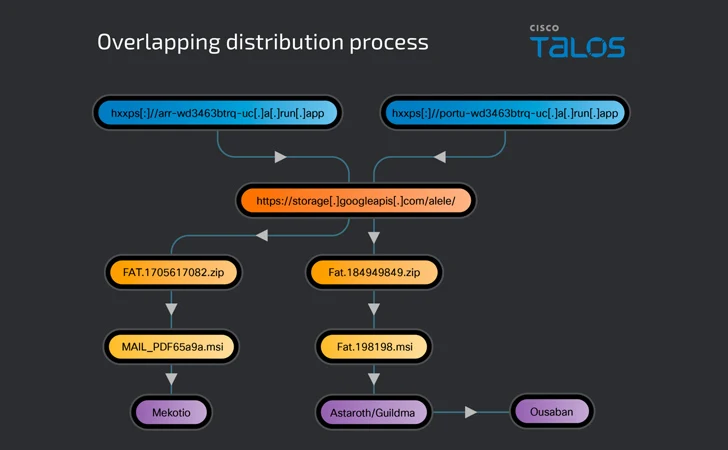

High-volume malware distribution campaigns, observed since September 2023, used the same storage bucket within Google Cloud for propagation, suggesting potential links between the threat actors behind the distribution campaigns.

Google Cloud Run is a managed computing platform that allows users to run frontend and backend services, batch jobs, deploy websites and applications, and queue compute workloads without having to manage or scale infrastructure.

“Adversaries may view Google Cloud Run as a cheap but effective way to deploy deployment infrastructure on platforms that most organizations likely do not block from accessing internal systems,” the researchers said.

Most of the systems used to send phishing messages come from Brazil, followed by the United States, Russia, Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador, South Africa, France, Spain and Bangladesh. The emails contain themes related to invoices or financial and tax documents, which in some cases purport to come from local government tax agencies.

Embedded in these messages are links to a running hosted website[.]app, resulting in the delivery of a ZIP archive containing a malicious MSI file directly or via 302 redirects to a Google Cloud Storage location, where the installer is stored.

Threat actors were also observed attempting to evade detection using geofencing tricks by redirecting visitors to these URLs to a legitimate site such as Google when they accessed them with a US IP address.

In addition to leveraging the same infrastructure to transport both Mekotio and Astaroth, the infection chain associated with the latter serves as a conduit to distribute Ousaban.

Astaroth, Mekotio and Ousaban are all designed to target financial institutions, keeping tabs on users’ web browsing activity, as well as logging keystrokes and taking screenshots in case one of the targeted bank’s websites is open .

Ousaban has a history of using cloud services to its advantage, having previously used Amazon S3 and Microsoft Azure to offload second-stage payloads and Google Docs to retrieve command and control (C2) configuration.

The development occurs in the context of phishing campaigns that propagate malware families such as DCRat, Remcos RAT and DarkVNC capable of collecting sensitive data and taking control of compromised hosts.

It also leads to an increase in threat actors using QR codes in phishing and email-based attacks (also known as quishing) to trick potential victims into installing malware on their mobile devices.

“In a separate attack, hackers sent targets spear-phishing emails with malicious QR codes pointing to fake Microsoft Office 365 login pages that ultimately steal the user’s login credentials once entered,” Talos said.

“QR code attacks are particularly dangerous because they shift the attack vector from a protected computer to the target’s personal mobile device, which typically has fewer security protections and ultimately contains the sensitive information attackers are looking for.”

Phishing campaigns have also set their sights on the oil and gas sector to deploy an information stealer called Rhadamanthys, which has currently reached version 0.6.0, highlighting a constant stream of patches and updates from its developers.

“The campaign begins with a phishing email that uses a car crash report to trick victims into interacting with an embedded link that abuses an open redirect to a legitimate domain, primarily Google Maps or Google Images,” he said Cofense.

Users who click the link are then redirected to a website hosting a fake PDF file, which, in reality, is a clickable image that contacts a GitHub repository and downloads a ZIP archive containing the thief’s executable.

“Once a victim attempts to interact with the executable, the malware unpacks and initiates a connection with a command and control (C2) location that collects any stolen credentials, cryptocurrency wallets, or other sensitive information,” the company added .

Other campaigns have abused email marketing tools like Twilio’s SendGrid to gain customer mailing lists and exploit stolen credentials to send convincing-looking phishing emails, according to Kaspersky.

“What makes this campaign particularly insidious is that the phishing emails bypass traditional security measures,” the Russian cybersecurity firm noted. “Because they are sent via a legitimate service and contain no obvious signs of phishing, they may evade detection by automatic filters.”

These phishing activities are further fueled by the easy availability of phishing kits such as Greatness and Tycoon, which have become a convenient and scalable means for would-be cybercriminals to mount malicious campaigns.

“Tycoon Group [phishing-as-a-service] it is sold and marketed on Telegram starting at $120,” Trustwave SpiderLabs researcher Rodel Mendrez said last week, noting that the service was first created around August 2023.

“Its key selling features include the ability to bypass Microsoft two-factor authentication, achieve “top-notch link speeds,” and leverage Cloudflare to evade antibot measures, ensuring the persistence of undetected phishing links.”