THE exploding The higher education bubble has finally dealt its first blow, and it’s a serious one. Several major public universities announced multimillion-dollar budget cuts in January, citing declining enrollment, among other factors. Pennsylvania State University expects to cut $94 million from its budget starting in July 2025 University of Connecticut (UConn) announced significant budget cuts in response to a projected $70 million deficit. And the University of New Hampshire (UNH) will reduce expenses by $14 million.

These cuts were a long time coming—higher education is facing a inscription cliff, even as it continues to spend on administration and student services like there’s no tomorrow. Pandemic-era emergency funding failed to delay the reckoning for any time. While university administrators are quick to blame state governments for providing insufficient funding, state lawmakers should remain steadfast in applying fiscal discipline to universities. There is still a long way to go to make higher education cost-effective.

Although university administrators and faculty Considering these budget cuts are nothing short of catastrophic for university activities, some cuts appear quite reasonable. For example, Pen State plans to scale back branch campus operations and cut duplicative programs. This is a necessary step in the right direction—Pennsylvania is known as “state with too many campuses,” and steep enrollments are decreasing on branch campuses justify reducing their operations.

But even when the right decisions are made, universities are too trepidatious. UNH, for example, will cut some programs at its Aulbani J. Beauregard Center for Equity, Justice and Freedom. However, they have not indicated whether only staff or the entire department will be cut. This is nowhere near enough: Not only are diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) administrative units like the Beauregard Center useless and expensive, they are also harmful to the campus environment. DEI initiatives have led universities to monitor what students and faculty say bias reporting systems and filtered hiring of teachers based on race and political opinions. Budget cuts should not be necessary to reduce these departments—they should never have been created in the first place.

Instead of making further cuts to redundant administrators, UNH rushed to shut it down 60 year old art museum. The museum housed works of art that teachers regularly incorporated into lessons. Some estimate that the art museum was barely operating less than $1 million annually. The university could have made cuts to other departments before attacking a key academic institution. Notably, UNH spends more than 1 million dollars on the basic salaries of DEI staff only. This estimate is conservative: it excludes benefits, departmental costs, and other university roles related to DEI.

UConn’s drastic approach also demonstrates the misguided priorities of higher education leadership. They announced 15% cuts. at all levels, to be distributed equally over the next five years across all units, including administration. This approach might seem more “equitable,” but it is based on the incorrect assumption that waste is concentrated equally in all parts of the university. We know this isn’t true: report after report has discussed the problems administrative bloat AND extravagant services for students. There is no need to focus on core educational functions when there is more low-hanging fruit.

These budget cuts have revived long-standing struggles over public subsidies to higher education institutions. Leader a Pen State AND UConn they publicly denounced their state legislatures for failing to fund the desired amounts. UConn has discussed raise tuition and Penn State refuses to engage to freeze tuition even if their funding requests are met. The arguments refer to the finished debates state disinvestment in higher educationin which universities argued that exorbitant tuition increases in recent decades had less to do with massive growth in student loan availability and more to do with shrinking state funding.

But the facts simply don’t match the administrators’ narrative. In UConn’s case, the reduction in state funding is not so much a funding cut as a return to pre-pandemic realities. As of 2020, the Connecticut state government has been using pandemic relief funds provide emergency support to its public universities. Relief funds are expected to run out in 2025, and the state has not agreed to cover the gap. This makes the current situation inevitable: The pandemic-era relief funds were temporary, but UConn apparently budgeted as if they were permanent.

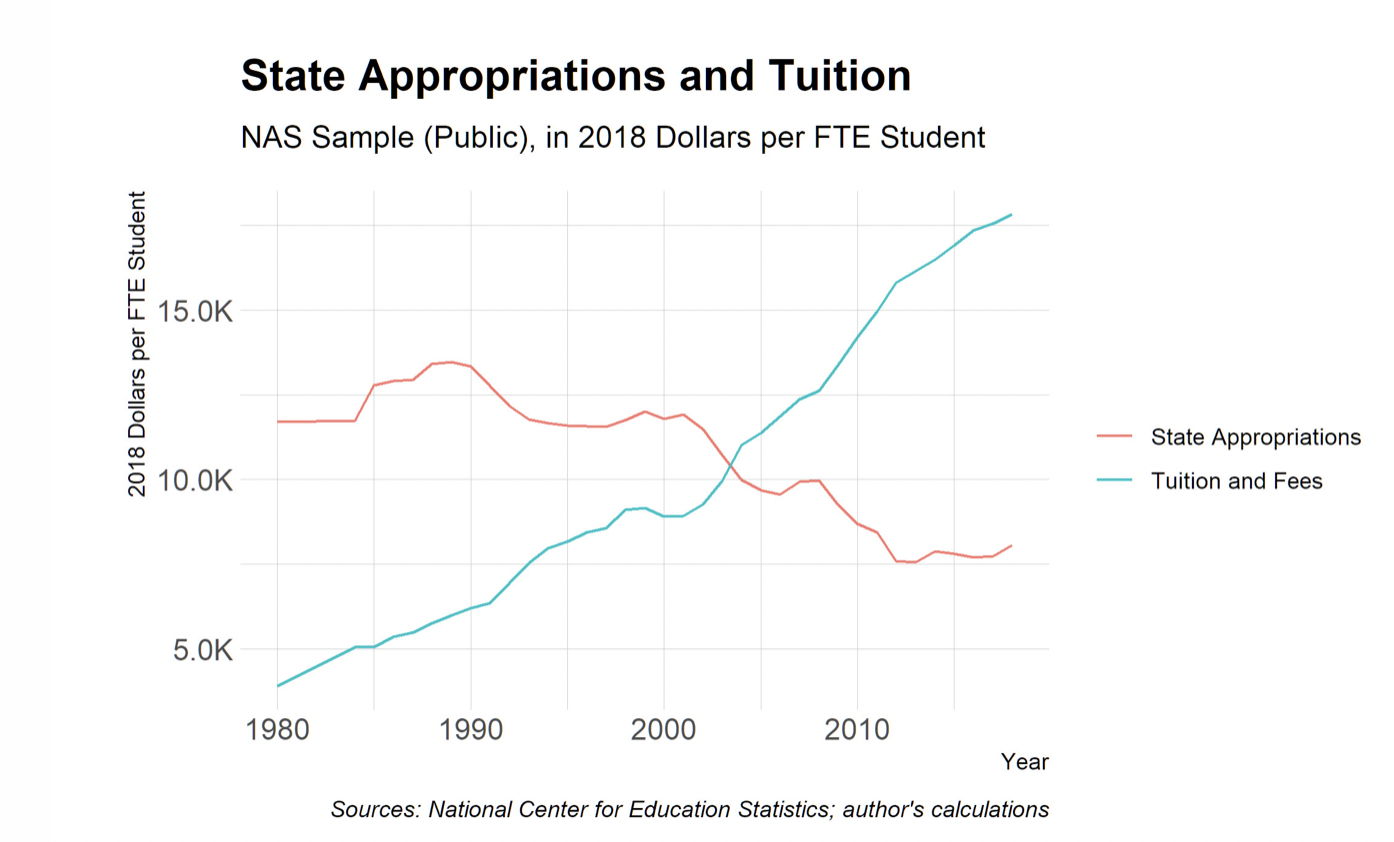

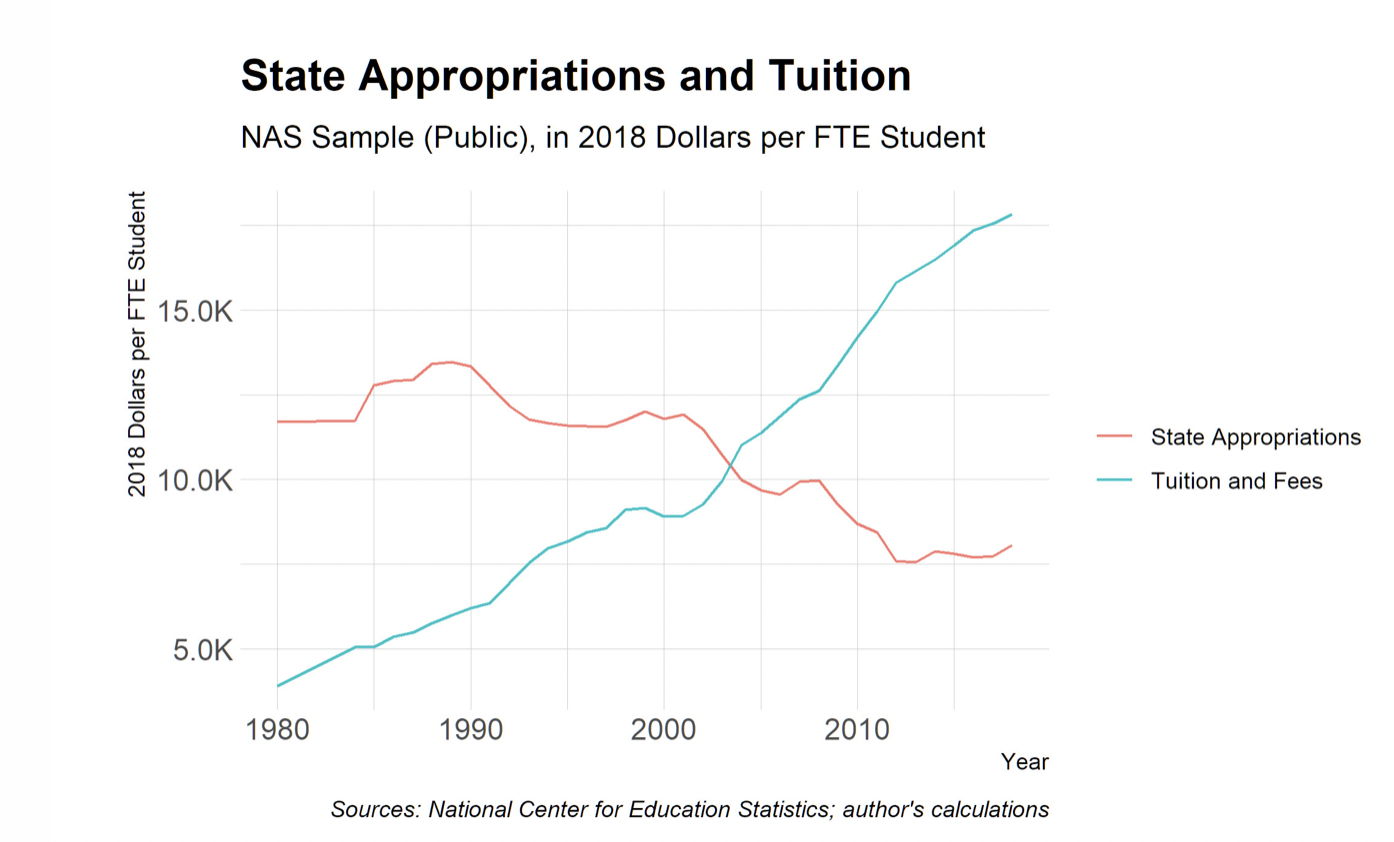

As for tuition increases, a report from the National Association of Scholars found that even as state funding per student decreased by nearly $4,000, public universities increased tuition by nearly $14,000 per student. The decrease in state funding alone is not enough to explain the increase in tuition. What explains the rise in tuition is the rapid increase in college expenses. This is why implementing budget cuts is critical.

As higher education mourns, taxpayers should welcome budget cuts. Restoring fiscal discipline, while painful at the moment, is the only way to permanently heal our higher education system.