A Georgia prison refuses to ship all books to inmates except those from major retailers. A local bookstore has sued, claiming the policy is unconstitutional.

In May 2023, two different people visited Avid Bookshop, an independent, progressive bookstore located in Athens, Georgia. Each customer purchased three books to ship to an inmate at the Gwinnett County Jail. Both packages were returned, with prison paperwork stating the reason “Not from Authorized Publisher/Retailer.” Shoppers asked Avid if the store could ship books directly.

Each time, Luis Correa, Avid’s operations manager, packaged new paperback copies of the same books and shipped them directly from the store. Aware of the prison’s stated policy that shipments “must have a packing slip or receipt indicating what is in the package,” Correa included both. (Correa declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Once again, the packages came back, with a sticker saying they were “not sent by the publisher or authorized reseller.”

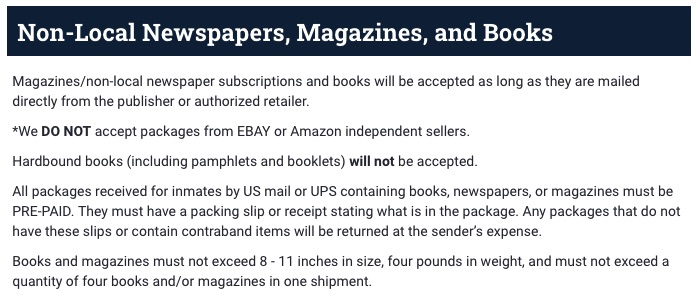

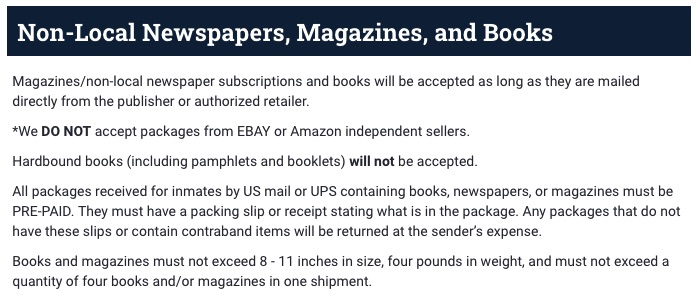

The Gwinnett County website states that “subscriptions to non-local magazines/newspapers and books will be accepted as long as they are shipped directly from the publisher or authorized reseller,” but provides no clarification on what an authorized reseller is or how to become one.

Correa contacted the prison to ask why it was rejecting Avid’s shipments. The indictment alleges that a deputy then advised that “since Avid was a local bookstore, friends and family could come into the bookstore and insert contraband into the books that were sent to prison.” The congressman also noted that the prison only accepts packages from Amazon and Barnes & Noble, but added that “even Barnes & Noble we have had problems with them.”

This is patently unconstitutional, says Atlanta civil rights attorney Zack Greenamyre. “Avid exists so we can communicate through books with other people,” Greenamyre says Reason. “That certainly includes people who are in custody, perhaps most importantly. And the government is telling them that they can’t engage in their expressive conduct, without good reason.”

Avid pressed the issue, trying to appeal the “authorized reseller” policy. In an email response, Dan Mayfield, general counsel for the Gwinnett County Sheriff’s Office, which runs the jail, said the policy is in place “to ensure resident associates cannot immerse pages in drugs or otherwise create security issues. We cannot approve libraries, like Avid, that are open to the public.”

Texas prison officials say inmates are receiving shipments of paper laced with drugs such as fentanyl or synthetic THC. Testifying before the New York City Council in October 2022, New York Department of Corrections Commissioner Louis Molina explained how fentanyl enters the city’s prisons: “Most of it enters in letters and packages laced with fentanyl, literally soaked in the drug, and shipped to people in custody,” at which point the inmates “smoke it, chew it, or snort it off the paper.”

“Are Texas officials suggesting that book pages are saturated with THC and that inmates tear out the pages and lick or ingest them?” asks Jeffrey Singer, a practicing physician and senior fellow at the Cato Institute. “I’ve never heard of anyone doing this, and I’m not sure how effective it would be.” He says Reason that inmates could theoretically use THC-infused paper to “roll loose tobacco cigarettes and kick them,” but “the prison may prohibit prisoners from using rolling tobacco.”

“Huff [fentanyl] removing it from the paper would be more challenging since it is presumably embedded in the paper, not powder-like, and useful for snorting,” Singer adds. “I don’t know if any of these things have ever happened, or if law enforcement is simply imagining such scenarios.”

It is also worth noting that most contraband into Texas prisons was smuggled in by staff. In December, a federal grand jury indicted 13 defendants for trafficking narcotics into Texas prisons, including three correctional officers.

Avid sued the Gwinnett County Sheriff and Jail Commander, seeking “a declaratory judgment that the Gwinnett County Jail’s licensed retail policy violates the First and Fourteenth Amendments” as well as “nominal damages and compensatory”. Greenamyre represents Avid in his lawsuit.

The lawsuit, filed in March, claims that the “authorized retailer” policy is “not reasonably related to a legitimate criminal interest,” as is the distinction that allows Amazon or Barnes & Noble to ship books to prison but not to a bookstore smaller. “Avid can ship new books to prison residents” from its own warehouse “without any member of the public having had access to the books,” just as Amazon would, the lawsuit says.

The lawsuit also claims that, in response to an open records request, the county did not “produce any documents relating to incidents of contraband found inside books shipped to the Gwinnett County Jail.”

Unfortunately, censorship by prison authorities is nothing new: As ReasonCJ Ciaramella wrote in 2018: “State prison systems ban thousands and thousands of books.” Texas, for example, had banned 10,000 individual stocks.

According to a database published by The Marshall Project, Georgia prisons have banned 28 specific book titles. The banned list ranges from theoretically reasonable inclusions, such as Hacking for Mannequins OR The Big Book of Serial Killersto the bizarre, kind of The giant book of vampire novels 2 or the Fifty Shades of Gray series. Georgia prisons have also banned the Quran, which similarly appears to be a violation of the First Amendment.

AND Reason has experienced its own share of prison censorship: Most recently, a subscriber incarcerated at FMC Devens, a federal prison in Massachusetts, was barred from receiving the magazine’s October 2023 issue. That issue’s cover story detailed how federal corrections officers were not prosecuted even after admitting to sexually assaulting inmates at the Florida women’s prison where they worked.

According to a rejection letter from FMC Devens, “such material jeopardizes the good order and security of the institution.”