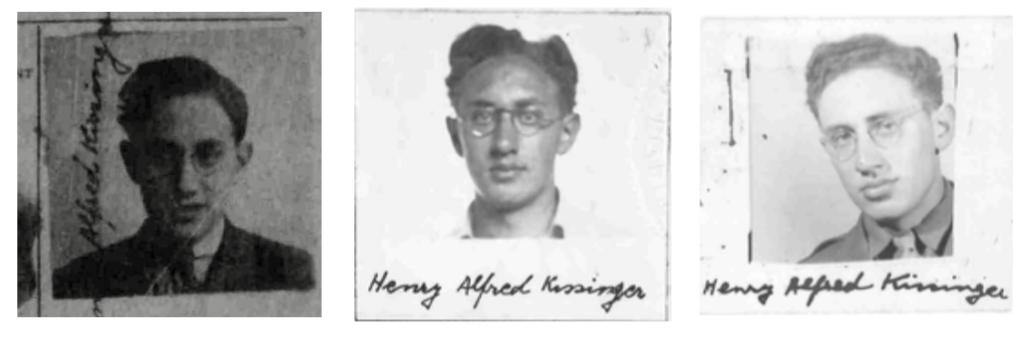

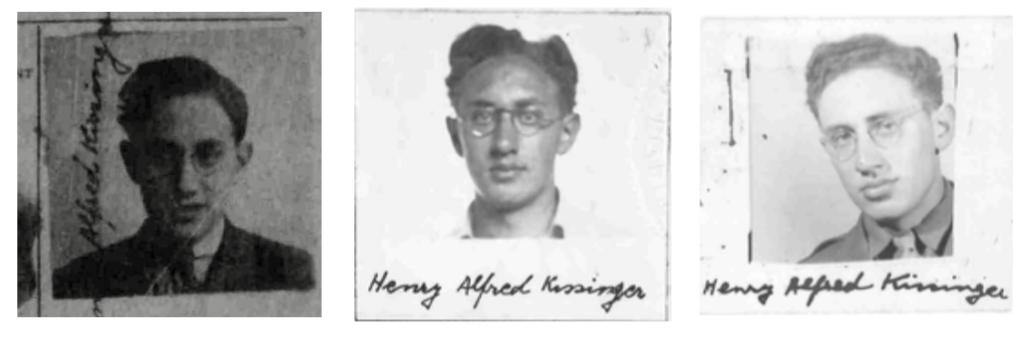

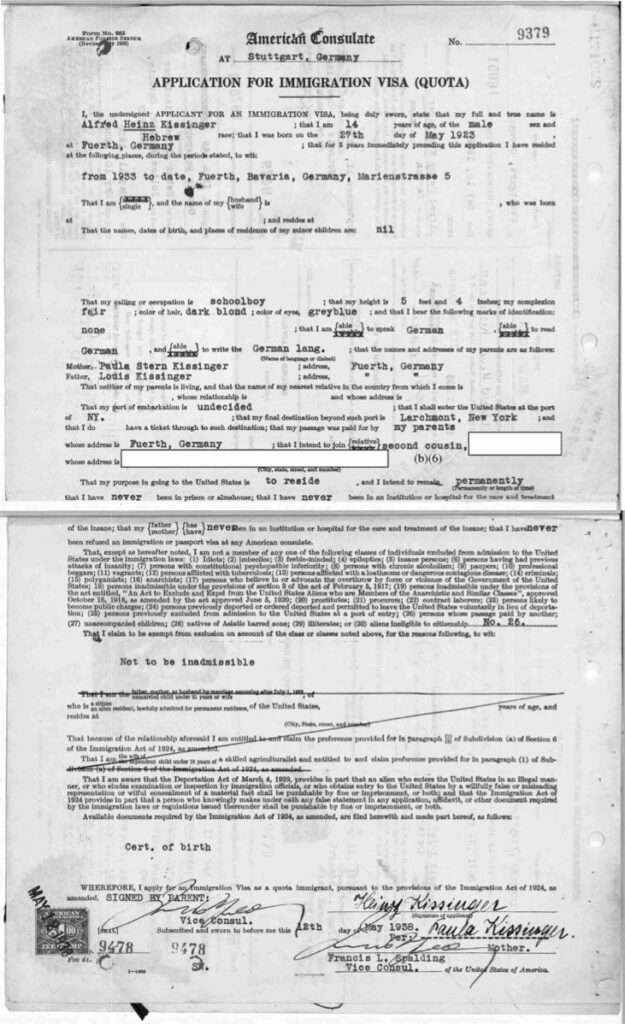

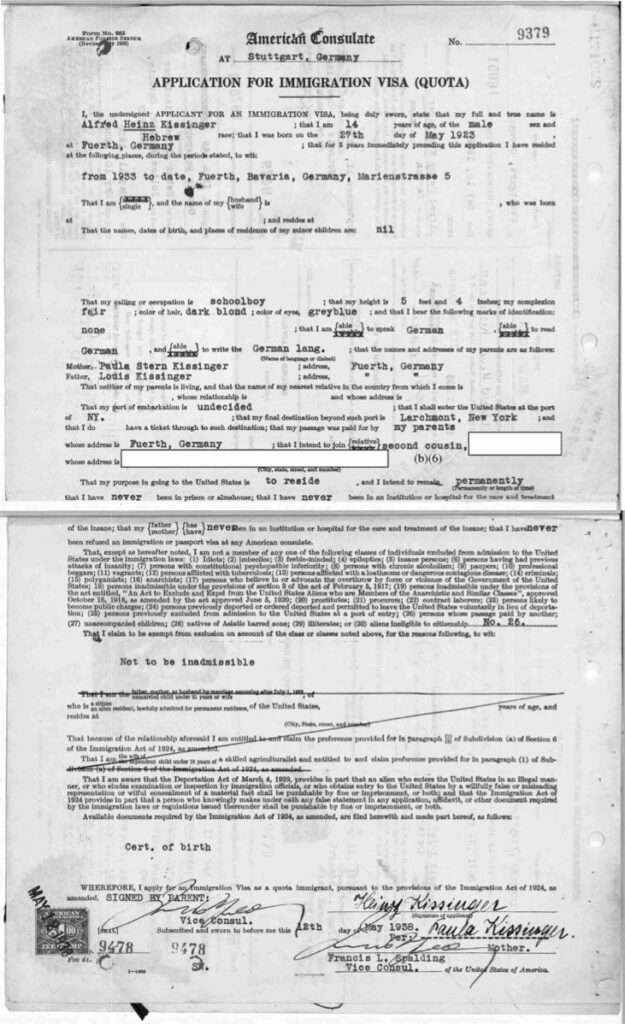

Before he became America’s most controversial secretary of state, Henry Kissinger was a refugee boy named Heinz from Fürth, Germany. He had the sullen look of a teenager, with a hint of mischievous curiosity. His birth certificate bore the swastika emblem of the Nazi German state, but his visa application said he was “of the Jewish race,” a very good reason to leave Germany at the time.

Six months after Kissinger’s parents submitted their request to the American consulate in Stuttgart, and two months after the family’s arrival in New York, the Nazi government canceled all German Jews’ passports. Kissinger had just escaped a genocide.

Reason obtained an exclusive copy of Kissinger’s immigration file under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). It includes both his original entry documents from the 1930s and his naturalization forms from the 1940s. The documents provide intimate snapshots of Kissinger’s early life, when he was beginning to realize the power and danger of politics, but before he took that power for himself.

If Kissinger was a mischievous boy when he applied for the visa, he was a world-weary man by the time he obtained American citizenship. Photos attached to various forms over the years show Kissinger’s face becoming more mature, his gaze more alert, his adolescent mischief more toned down.

Those images were almost lost forever. Shortly after Kissinger’s death last year, I sent FOIA requests to several federal agencies for its files. (The Privacy Act prevents the government from releasing data on living citizens, but anyone can ask for data on the dead.) The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said it could not find Kissinger’s file. When I complained in a (now deleted) tweet, the FOIA office suddenly said that his file had appeared.

The key details contained in the archives are well known to Kissinger’s biographers. He was drafted into the United States Army in 1943 and became a naturalized American citizen during his basic training at Camp Croft in South Carolina.

Kissinger’s talent was quickly recognized, and the army promoted him to counterintelligence officer in charge of denazifying German territory. This set him up well for a meteoric rise through government during the Cold War.

During his military service, Kissinger stopped calling himself “Heinz” and began calling himself “Henry”, a fact that was noted in his naturalization application. He then said that military service was a “process of Americanization.”

This process was much simpler in the 1940s. To obtain the visa, Kissinger’s parents had to provide some basic biographical information and provide the address of a cousin in New York.

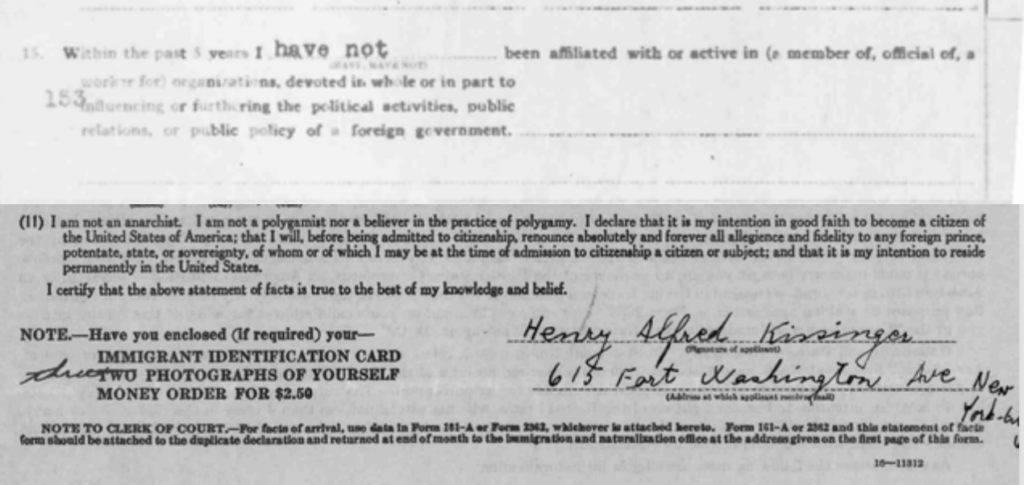

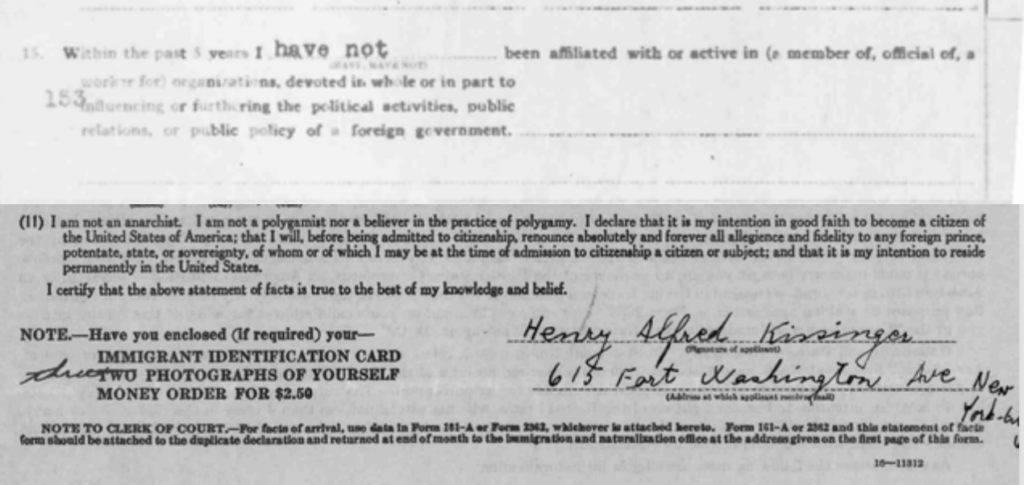

To become a citizen, Kissinger had to list all trips out of the country and swear that he was not an “anarchist,” a “polygamist,” a foreign agent, or otherwise loyal to any “foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty.”

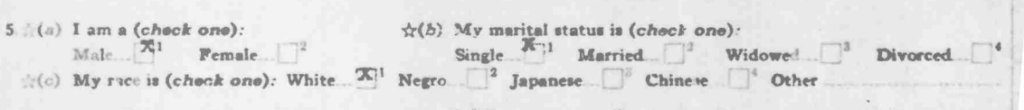

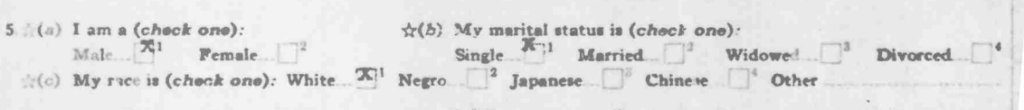

Some of the form fields today are decidedly outdated. The U.S. forms offered five racial categories to choose from: “White,” “Negro,” “Chinese,” “Japanese,” and “Other.” And, of course, today’s Germany would not classify its citizens based on membership of the “Jewish race.”

Kissinger’s entire immigration file – including his visa application, his alien identification card, his military background check and his citizenship documents – are only 50 pages in total. It took him five years after his arrival to become a U.S. citizen. Compare thousands of pages of documents and decades of waiting we need it today.

Ironically, Kissinger became an advocate of closing the door on others. He was infamous caught on tape telling then-President Richard Nixon in 1973 that “emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union is not an American foreign policy goal, and if they put Jews in gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern.”

In a October 2023 interview to a German journalist, Kissinger said that “it was a grave mistake to let in so many people of totally different cultures, religions and concepts, because it creates a pressure group within every country that does this.” He died the following month.

It’s hard to imagine that a young Heinz Kissinger knew where he would end up in a few decades: telling the most powerful man in the world not to worry about Jewish refugees. Or that he knew that his last public act would be to rail against diversity on German television.

But this is America. Anyone can reinvent themselves as they prefer.