As I looked at the gigantic, fantastic, triumphant, overwhelming, punishingly large and loud Duna: second part in IMAX earlier this week, I couldn’t help but think of an old meme.

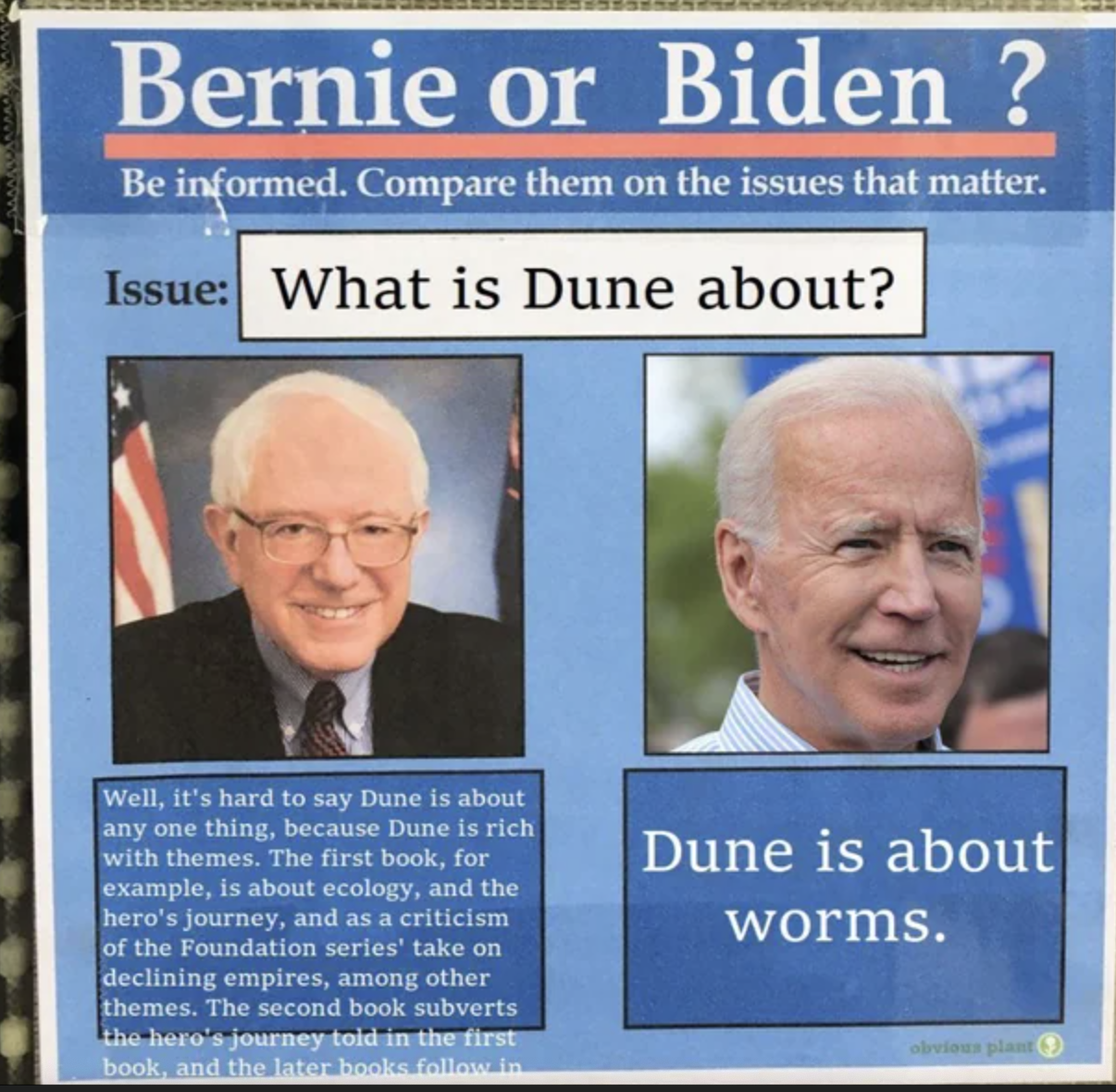

Some time before the 2021 release of Duna: first part, a clever anonymous poster teased a “know your candidates” page featuring Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. Except the “issue” they were discussing wasn’t healthcare or foreign policy. It was “What is Dune about?”

In the meme, Sanders’ response was typically long-winded and discursive: “Well, it’s hard to say that Dune is about any one thing, because Dune is rich in themes. The first book, for example, is about ecology, and the hero’s journey, and as a critique of the Foundation series’ approach to declining empires, among other things. The second book subverts the hero’s journey told in the first book, and the subsequent books follow…” and then the false response of Sanders fades on the page.

The meme version of Biden responds simply: “Dune is about worms.”

The magic of director Denis Villeneuve’s two-part adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel is that it captures both false candidate responses from the meme. It is an intricate desert epic about ecological balance, the harshness of nature, the economics of resource extraction, imperialism, tribal politics, corporate intrigue, psychedelic drugs, culture clash, and science fiction. Golden Age that misses the point, among other things.

But it’s also about, you know, worms.

Specifically: a lot, Very big worms.

Even more than the first film, which covered just over half of Herbert’s novel, Duna: second part it is a showcase for cinematic grandeur, for films as conveyors of pure, terrifying enormity. The film is the story of young Paul Atreides, a young duke whose family was killed by rival Harkonnens after a distant emperor granted the Atreides charge of the planet Arrakis.

Arrakis is no ordinary planet: it’s the home of spice, a psychedelic drug that also appears to fuel interstellar travel, produced by the planet’s native giant sandworms. He imagines if oil was also LSD and was produced by wandering, killer whales living deep in the desert sands.

The first installment was the story of Atreides’ journey to Dune and the defeat of his family. The second is the story of his triumphant revenge, as he unites the local population, the Fremen, in defiance of the Harkonnen lords.

Herbert’s novel is filled with descriptions of corporate structures and corporate strategy discussions of economic fundamentals and resource extraction parameters, all mixed with complex political machinations and semi-inscrutable hallucinogenic dream logic with religious prophecies and drug-addled visions , plus lots of asides from the nifty sustainable eco-technology of life on a barren sandy planet. Sometimes, reading Dune resembles reading the minutes of a corporate board meeting while bantering with green tech climate activists in the desert.

Anyway, you can probably figure out what the Bernie-meme was talking about.

The film, however, captures all this awkward complexity quite well, capturing desert life among the Fremen and pointing to their political structures and religious beliefs without subjecting viewers to prolonged exposure. Villeneuve and co-writer Jon Spaihts understand that a carefully imagined fictional world doesn’t need to constantly pause to explain itself; he can just go about his business.

But then, in the midst of all this, there are worms. In contrast with Duna: first part, which ended with a hint of possibility, this time Paul Atreides will be able to ride them. And this is Exceptional.

In Duna: second part, Villeneuve delivers a handful of truly gigantic set pieces featuring the skyscraper-sized sandworms of Arrakis as they plow through the desert of the film’s alien planet. Along with his work on the First Contact film I arrivemark Villeneuve as Hollywood’s most successful purveyor of colossal mysteries.

As with that film’s obelisk and its tentacled alien inhabitants, there’s something truly alien about the sandworms of Arrakis, and also a sense of scale and vastness that few other filmmakers convey. Watching a sandworm dive through desert valleys, exploding waves of sand in its wake, on a large IMAX screen with knee-shaking surround sound is the kind of audiovisual experience that high-brow films were created for. budget and on the big screen. Duna: second part it’s a glorious, overwhelming sensory buffet.

In recent years, too many blockbusters have served up weightless, ugly, computer-generated, and at best mediocre scenes. That of Villeneuve Dune the films resemble what real cinematic spectacle looks like. They’re movies about worms, really big worms. Hell yes, I am.